Endresen's vocals sound unnervingly close to those of folk-rock singer Sandy Denny on this song cycle of sorts, originally commissioned by a Norwegian jazz festival. Themes of traveling and a vaguely mythic air (the songs were originally titled "Pagan Pilgrimage") predominate, but the chief pleasures are the haunting and resonant qualities of Endresen's voice.

aCá

Sunday, June 30, 2013

add 0401 lost tribe

Lost Tribe's provocative mix of jazz, funk, progressive rock, heavy metal, and hip-hop is well represented on this 1994 disc. There are moments during "It's Not What It Is" when the '80s rock stylings of Living Color come to mind. Other tracks, such as "Second Story" and "Fuzzy Logic," recall the frenetic, rap-influenced sound of early Steve Coleman and Five Elements. Guitarist Adam Rogers and saxophonist David Binney seem to be the resident metalheads -- witness Rogers' crushing "Steel Orchards" and Binney's avant-thrash composition "H." Former Five Elements guitarist David Gilmore joins Rogers throughout the disc, making for some hot dual guitar work. Bassist Fima Ephron lays down rap vocals on his own "Walkabout," as does drummer Ben Perowsky on his own, less convincing "Daze of Ol'." On a mellower note, "Room of Life" and "La Fontaine" feature a more harmonically colorful side of the band.

aCá

aCá

add 0400 bonamassa - Hart

Fans of guitar master Joe Bonamassa will be delighted that 2011 was such a prolific year in his career. First came the fine, rootsy Dust Bowl, then 2, the second chapter in his Black Country Communionproject's catalog. Don't Explain, a collection of soul, blues, and jazz-oriented covers in collaboration with vocal firebrand Beth Hart marks his third entry this year. The ten-song set of blues and soul is a logical extension of her vocal contribution to "No Love on the Street" from Dust Bowl. Opening is a thoroughly raucous contemporary blues reading of Ray Charles' "Sinner's Prayer," followed by a quirky version ofTom Waits' "Chocolate Jesus," and an unusual cover of contemporary jazz-pop singer/songwriterMelody Gardot's "You Heart Is as Black as Night." On this cut, a string orchestra adds a touch of perversity; it offers the impression of a femme fatale singing a Brecht-Weill number in a smoky cabaret in front of a moody string orchestra, buoyed by a brooding electric blues quintet. "For My Friends," a Bill Withers' tune, is a big, nasty, jagged blues number that keeps the funky groove intact. The title track, a number closely associated with Billie Holiday, falls flat. Hart tries too hard to employ Holiday's phrasing, the string orchestrations are overblown, and Bonamassa's crew is too reverent. This formula also mars the remake of Aretha Franklin's "Ain't No Way" that closes the set. Far better are readings of Etta James' signatories "I'd Rather Go Blind," and "Something's Got a Hold on Me." Hart's emotive, throaty delivery is perfectly suited to both songs, and she resists trying to ape James' phrasing. Since they follow one another directly, the musical difference between them also showcase's Hart's diverse abilities. The former is a soul burner, the latter a gospel blues. Bonamassa and band accent her every phrase with requisite rowdiness, sting, and grit. The pair's only vocal collaboration is a burning read of Delaney & Bonnie's "Well, Well." With Anton Fig's breaks and rim shots underscoring Arlan Scheirbaum's electric piano fills,Bonamassa's burning leads, the chunky, rhythmic foundation from guitarist Blondie Chaplin, andCarmine Rojas' bassline, Hart and the lead guitarist trade whip-smart call and response vocals with enough raw country-soul to bring the song to a new audience. While not a perfect recording, Don't Explain is a good one, whose strengths are numerous enough to warrant a second go round.

aCá

aCá

add 0399 bill frisell

Bill Frisell's Big Sur, on Sony's resurrected Okeh imprint, collects 19 individual pieces in a suite commissioned by the Monterey Jazz Festival. He spent ten days in retreat at Big Sur's Glen Deven Ranch, where he composed most of it. His band on this date includes his 858 Quartet -- Jenny Scheinman: violin; Eyvind Kang: viola; Hank Roberts: cello-- and his drummer Rudy Royston; Kangand Royston are from his Beautiful Dreamers group, making this an unorthodox string quartet with drums. Those drums not only keep things grounded and earthy, they add force, dimension, and dynamics even on the ballads. As is typical for Frisell's ensembles, it's not about soloing so much for these players -- though all are given opportunities -- as the strength of the work through the voice of the group, withFrisell's guitar as the unifying factor, whether it's in the opening waltz "The Music of Glen Deven Ranch," the slowly unfurling, darkly tinged ballad "Going to California," or "The Big One," which references surf rock. There is a five-note vamp the guitarist uses in several pieces here as a way of bringing the listener back to the fact that despite the varying nature of these pieces, they make up a significant whole. "We All Love Neil Young" is a duet for Frisell and Kang with the violist taking up the "vocal" part as the guitarist fills and weaves through his lines. The gradually unfolding nature of "Highway 1" is an excellent and wonderfully quirky showcase for Scheinman and Kang in dialogue, and for the staggered use of dissonant harmony as Frisell's effects. The title track is a wonderful showcase forRoberts, while "The Animals," though brief, offers fine interplay between the violinist and violist as they weave through Frisell and Roberts with a Celtic-tinged folk music. "Hawks" is the most driven thing on the record, though it flirts with classical and folk music by turns, and in and out statements by all group members, driven by Royston, offer a deft quickness that gives the impression of flight. While the aforementioned tracks are noteworthy examples, this hour-long work is at its absolute best when taken as a whole. On Big Sur, Frisell delivers an inspired musical portrayal of the land, sky, sea, and wildlife of the region with majesty, humor, and true sophistication.

aCá

aCá

Friday, June 28, 2013

add 0398 cinematic

For the true follow-up to 2002's Every Day -- since 2003's Man with a Movie Camera soundtrack had actually been recorded four years earlier -- J. Swinscoe & co.'s Cinematic Orchestra produced another soundtrack, this one virtually invisible. Not long after Every Day's release, Swinscoe began writing music for another Cinematic LP, but in another direction from where he'd gone previously. This was a series of quiet, contemplative instrumentals, with Rhodes keyboards and reedy clarinets, simply begging for a narrative (call them orchestrations for cinema). With scripts for each supplied by a friend -- each track got its own story, together comprising different scenes from a single life -- and a series of unpeopled photographs supplied by Maya Hayuk, Cinematic Orchestra had the narrative they needed for their invisible soundtrack. (Added vocals from Fontella Bass, Lou Rhodes, and Patrick Watson represent the same person at different ages.) The results form an intensely affecting record, but one whose monochromatic format unfortunately serves no large purpose; when every song attempts to become a mini-masterpiece of melodrama, patience grows thin. Swinscoe tells us that he wanted to record an album where "leaving the spaces as empty as possible was paramount," but he can hardly complain if we choose to leave him the space to himself.

aCá

aCá

add 0397 cinematic

Whether to categorize Motion as a jazz or electronica album is an intriguing conundrum, because it truly turns out to be a combination of both musical forms, and it is an unequivocally brilliant combination, at that. British arranger/programmer J. Swinscoe -- who virtually is the Cinematic Orchestra -- gathered samples of drum grooves, basslines, and melodies from various recordings and artists that have inspired and influenced him (spaghetti-western composer Ennio Morricone and Roy Budd's spy film scores, '60s and '70s jazz and soundtrack scores from musicians such as Elvin Jones, Eric Dolphy, Andre Previn,David Rose, and John Morris). He then presented the samples that he had collected to a group of musicians, the core of which consisted of Tom Chant (soprano sax, electric and acoustic piano), Jamie Coleman (trumpet, flugelhorn), Phil France (bass), and T. Daniel Howard (drums), to learn and then improvise. Those tracks, in turn, were sampled and rearranged by Swinscoe on computer to create the tracks that make up this first Cinematic Orchestra album. The album bears all of the atmospheric hallmarks of ambient electronica, as well as Swinscoe's soundtrack inspirations and all the improvisational energy of jazz. Most of the songs are built with wave upon wave of repeated loops and instrumental phrases that work into a groove. Yet it feels at any moment as if the music is about to explode, like a steam whistle boiling to its screaming point. On "One to the Big Sea," for example, the same four-note bassline plays over and over with the same ride cymbal rhythm, but instead of seeming rote or mechanical, the riff just seems to continually bubble up and throb, slowly building anticipation and pressure. When a looped piano riff and horn charts enter the music, the juxtaposition seems almost jarring; yet, as they continue to repeat, in turn, atop the bass and cymbals, you can't help but feel that you're waiting for another dramatic leap, which eventually comes by way of the song's cornerstone: a thrilling drum solo. Each song is just as accomplished in its own way, so expertly arranged by Swinscoethat the impression of both structure and improvisation is created, while never sounding for a moment anything less than organic. The music is constructed piece by piece until it is a seamless whole that lives and breathes on its own merits, much like the soundscapes of DJ Shadow. Regardless of how they were made, though, the songs on Motion are by turns eerie, lush, edgy, expansive, gritty, intensely powerful, and gorgeous. Sometimes an album comes along that forces you to reconfigure and re-evaluate all of the assumptions you had previously made about music in order to realize how vast and endless the possibilities are; this is one of those albums.

aCá

aCá

Thursday, June 27, 2013

add 0396 Bill Frisell

For all the self-generated hype that Tzadik releases carry on their spine inserts, the one that accompaniesBill Frisell's Silent Comedy is pretty close to accurate. This really is the guitarist as you've never heard him before -- at least on record. He's improvising live in a studio with no edits or overdubs. Some of the 11 pieces included here carry traces of his signature bell-like tone, but this is a very free recording. The set's longest cut, "John Goldfarb, Please Come Home," is a meld of spaced-out sonic effects, harmonic invention, skeletal phrasing, and aggressive skronk that moves from halting melody to pure dissonance. Despite "Lake Superior"'s pastoral title, the cut is anything but; it's a monstrous Wall of Sound with digital and analog effects meddling around on a drone and employing a full range of distortion and feedback. Using a very limited harmonic palette, Frisell's guitar alternately takes on the tones of a harmonium, a Wurlitzer, and chimes to offer elemental sound contrasts that almost feel like counterpoint -- all in a gorgeous wail. While "Proof" is more conventional, with Frisell's instantly recognizable tone investigating a vamp from all sorts of musical viewpoints, the very next cut, "The Road," utilizes a broad array of tools in his effects box to create a restrained drone as the tonal backdrop, while a wah-wah offers a repetitive bassline melody but then breaks it down to an alternating series of small, moment-to-moment chord voicings, shimmering single notes, spacious delays, and even rumbling lower-string cascades woven together in a seamless fit. In the title track and in "Leprechaun," those effects are used with a requisite warmth and sense of humor. While "Ice Cave" walks a little too close to ambience for its own sake, "Big Fish" combines it with an inherent sense of melodic invention to create a tune that is nearly hummable, but traverses a fascinating musical terrain. This set will most likely appeal to guitar and improv freaks, as well as Frisell's most devoted fans. That said, given its intimate nature, it should resonate wider and deeper than that. He is doing things -- on the fly -- with his electric guitar and effects boxes that feel more like a conversation with a listener than merely an expression himself for his own sake.

aCá

aCá

add 0395 Beth Hart

Beth Hart received a considerable boost from her collaboration with guitarist Joe Bonamassa, but her 2013 album, Bang Bang Boom Boom, finds the blues-rock belter returning to her comfort zone, working with producer Kevin Shirley and running through a selection of songs that are originals; songs that emphasize Hart's range and power. In some ways, this is the purest record Hart has yet recorded; there is a real sense of what she can sing and how she lays back, waiting for the moment when her wailing would create the strongest disruption. That means Bang Bang Boom Boom feels familiar without being complacent: there is no surprise in style but rather in attack, how Hart waits for the precise moment to unleash her fury. Sometimes, it seems that Hart would be well-served by stretching herself just a bit, butBang Bang Boom Boom isn't an album that's meant to surprise. It's supposed to hit its mark with precision and minimal flair, and that's exactly what it does.

aCá

aCá

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

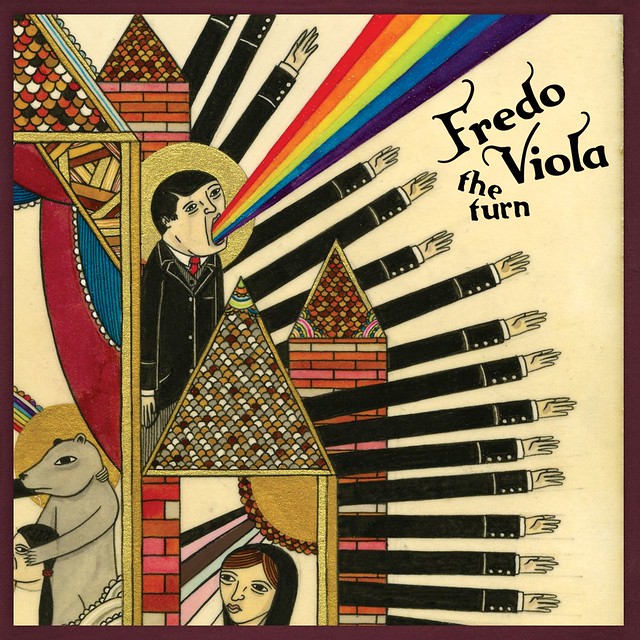

add 394 fredo viola

When a musician can boast such a command of melody and a voice of such soaring intensity as Fredo Viola, you could be forgiven for anticipating a record that's all too eager to stake out its comfort zone and defend it to the death. Yet while most singer/songwriters who know how to craft a tune are content to do just that, tipping the hat here and there to the sacred conventions of Nilsson, McCartney, and Wilson,Viola uses that facility purely as a launching pad for some of the most audacious and thrilling vocal arrangements to be heard on a pop record for many a year. Viola says he initially multi-tracked his voice to fill in for all the instruments he couldn't play. Yet in doing so he has inadvertently evolved a technique that, while it evokes sources as diverse as tribal chants, doo wop, Ligeti, Gregorian chant, and the Beach Boys at their most psychedelic, ultimately leaves you with that rarest of feelings -- that you are in the presence of something truly original. The Turn certainly contains enough evidence that, should commercial realities ever begin to bite, Viola could easily make his way as a master tunesmith. Even such two-minute pop marvels as "The Original Man" and "Friendship Is" are nevertheless brimming with harmonic and rhythmic twists. Yet while the voice is Viola's weapon of choice, his instrumental arrangements -- mostly keyboard-based -- are full of immaculately tailored sonic adventure. Only the strummed acoustic guitars of "Red State," a somewhat timid choice for a single, share a border with the merely humdrum. At its peak, however, The Turn is genuinely breathtaking. The title track is a thing of sinuous beauty, while "Robinson Crusoe"'s evocation of childhood games is one of the most uplifting slices of pure pop melody cloaked in luscious textures since "Penny Lane." Best of all is "Death of a Son," a pocket symphony that evolves from a state of choral grace to an exuberant celebration crackling with handclaps and (literal) fireworks. All told, The Turn is a triumphant reminder of pop's golden age, not in any nostalgic sense but in the way it captures that magical moment before commercialism and innovation became mutually exclusive concepts. So often in these days of bedroom studios, you get the feeling that experimentation is nothing more than a handy smokescreen for the inability to write a coherent melody. Fredo Viola is confirmation, if it were needed, that there's a very real distinction to be made between pushing envelopes for the sake of it and letting the imagination soar.

aCá

aCá

dd 395 Dan Auerbach

Whenever the lead singer/songwriter in a two-person group steps out with a solo album, the first question that comes to mind is whether the musician needed to go out on his own, whether he could possibly be constrained by his lone partner. In the case of Dan Auerbach, the guitarist and singer for the Black Keys, it's not so much that Pat Carney holds him back as that he's such a distinctive, powerful drummer that he colors and changes Auerbach's playing; it's what band chemistry is all about. Opening his own studio, Akron Analog, gave Auerbach an excuse to cut an album without Carney, and 2009'sKeep It Hid is at once completely similar and totally different than the Black Keys. All the same musical touchstones remain -- primarily classic post-WWII blues, often filtered through '60s and early-'70s classic rock -- but without Carney the attack isn't savage, focusing on feel instead of force. To a certain extent, the Black Keys followed that aesthetic on the Danger Mouse-produced 2008 LP Attack & Release, but "Keep It Hid" lacks its studied, self-conscious atmospherics, along with Carney's wallop. Auerbachcompensates by letting everything on "Keep It Hid" breathe -- there's space in his songs and his production, there are ragged edges, room echo, and natural distortion, all making it feel alluringly out of time. It follows that the album boasts more quiet acoustic moments than the Black Keys' records, but the difference is just as evident in songs that are closer to Auerbach's bluesy signature: "I Want Some More" has a thick, swampy rhythm that never quite gets menacing, "Heartbroken, In Disrepair" swirls, and the dramatic build of "When I Left the Room" has an almost psychedelic undertow, "Mean Monsoon" steps cleanly and precisely in contrast to the slow-crawling murk of "Keep It Hid," while the tremendous "My Last Mistake" is the poppiest song Auerbach has ever written. There's variety here, but Keep It Hid never draws attention to Auerbach's eclecticism, especially because it moves along at a rapid clip, never staying in one place too long. It all feels organic, right down to how it feels natural for Auerbach to step outside of the Black Keys to release this album: it really is something that he couldn't have made with Carney, and its existence winds up confirming the immense talents of both musicians.

aCá

aCá

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

add 393 Tomás Gubistch

Tomás Gubitsch

| Tomás Gubitsch | |

|---|---|

| Datos generales | |

| Nombre real | Tomás Gubitsch |

| Nacimiento | 1957 |

| Origen | Argentina |

| Ocupación | Compositor, Director de orquesta y guitarrista |

| Información artística | |

| Discográfica(s) | Le Chant du Monde / Harmonia Mundi |

| Artistas relacionados | Astor Piazzolla, Rodolfo Mederos, Luis Alberto Spinetta |

| Web | |

| Sitio web | Página Oficial |

Índice[ocultar] |

Primeros años[editar]

Tomás Gubitsch nació en 1957 en Buenos Aires, en una familia de intelectuales centro-europeos exiliados en Argentina poco antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Si bien creció en el ámbito de la música ‘clásica’ (Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler, Bartók, Stravinsky, Schönberg ou Ligeti), muy joven escucha también a los Beatles, Jimi Hendrix o Frank Zappa.

A los 10 años, su descubrimiento simultáneo de “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band” de los Beatles, y de “La consagración de la primavera” de Igor Stravinsky lo impulsa a tomar la decisión de ser músico.

A los 10 años, su descubrimiento simultáneo de “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band” de los Beatles, y de “La consagración de la primavera” de Igor Stravinsky lo impulsa a tomar la decisión de ser músico.

De Buenos Aires a París[editar]

En 1973, con 16 años, toca en su primera grabación profesional ("Cuasares", de Waldo Belloso) y firma inmediatamente su primer contrato con el label País4. Durante el mismo año, Tomás conoce a Rodolfo Mederos (bandoneonista post-piazzolliano) quien lo invita a integrar su grupo de tango contemporáneo, Generación Cero5.

El 1976, a los 18 años, Tomás Gubitsch es inmediatamente reconocido como un guitarrista virtuoso6 a partir de su entrada en el grupo de rock argentino Invisible —con Luís-Alberto Spinetta—, que convoca a más de 12.500 espectadores por concierto en el «Luna Park». .

A los 19 años, Ástor Piazzolla lo convoca para su gira europea de 1977, llenando l'Olympia (Paris)7 durante tres semanas8.

El periodista y ensayista Diego Fisherman escribirá 30 años más tarde que la meteórica carrera de Gubitsch en su país natal definió un nuevo standard en la historia de la guitarra en Argentina 9. Aparece como uno de los primeros constructores de puentes entre el universo del rock y el del tango 9 .

Esta primera etapa deja como testimonio tres discos generados por sus tres primeros encuentros musicales:

• El jardín de los presentes (Invisible, 1976)

• De todas maneras (Rodolfo Mederos y Generación Cero, 1976)

• Olympia '77 (Ástor Piazzolla y el Octeto Electrónico, 1977)

El periodista y ensayista Diego Fisherman escribirá 30 años más tarde que la meteórica carrera de Gubitsch en su país natal definió un nuevo standard en la historia de la guitarra en Argentina 9. Aparece como uno de los primeros constructores de puentes entre el universo del rock y el del tango 9 .

Esta primera etapa deja como testimonio tres discos generados por sus tres primeros encuentros musicales:

• El jardín de los presentes (Invisible, 1976)

• De todas maneras (Rodolfo Mederos y Generación Cero, 1976)

• Olympia '77 (Ástor Piazzolla y el Octeto Electrónico, 1977)

Terminada la gira con A. Piazzolla en marzo del 1977, la presencia del régimen totalitario en Argentina conduce Tomás a instalarse en París, cuna de la world music10 . Es el comienzo de varios encuentros y colaboraciones, implicándolo tanto como compositor e intérprete en grabaciones de obras de jazz, de tango, de world music, de música contemporánea, etc. Algunos ejemplos:

• Gustavo Beytelmann, Juan-José Mosalini, Osvaldo Caló y Jean-Paul Celea (Tango)

• Stéphane Grapelli, Michel Portal, Steve Lacy, Glenn Ferris, Jean-François Jenny-Clark, (Jazz)

• Luc Ferrari, Jean Schwarz y Michel Musseau (música contemporánea)

• Pierre Akéndéngué, Mino Cinélu, Nana Vasconcelos y David Dorantes (world music)

• Gustavo Beytelmann, Juan-José Mosalini, Osvaldo Caló y Jean-Paul Celea (Tango)

• Stéphane Grapelli, Michel Portal, Steve Lacy, Glenn Ferris, Jean-François Jenny-Clark, (Jazz)

• Luc Ferrari, Jean Schwarz y Michel Musseau (música contemporánea)

• Pierre Akéndéngué, Mino Cinélu, Nana Vasconcelos y David Dorantes (world music)

Carrera solista[editar]

A partir de 1979, Gubitsch comienza la composición de tres álbumes que forjarán su visión personal del tango actual:

• Resistiendo a la tormenta, (con Osvaldo Caló, 1980)

• Sonata doméstica (con O. Caló y Jean-Paul Celea, 1986)

• Contra vientos y mareas, (con O. Caló y Jean-Paul Celea, 1989)

• Resistiendo a la tormenta, (con Osvaldo Caló, 1980)

• Sonata doméstica (con O. Caló y Jean-Paul Celea, 1986)

• Contra vientos y mareas, (con O. Caló y Jean-Paul Celea, 1989)

Paralelamente, sus intereses artísticos se extienden a expresiones trans-disciplinarias y empieza a componer para el teatro, la danza y el cine. Avocado a diversos encargos de escritura musical, Tomás Gubitsch décide poner su carrera de guitarrista entre paréntesis para dedicarse por completo a la composición y la dirección de orquesta. Co-compone y co-dirige varios discos de música actual (Maurane, Jean Guidoni, Sapho...). Con Hughes de Courson, Tomás co-compone y co-dirige varios álbumes, entre los cuales Songs of Innocence (Virgin, 1999) elogiado por la prensa francesa, (Libération).

En 2004, retoma la guitarra y su carrera solista con un franco retorno al tango actual, compartiendo escenarios y grabaciones con los notables músicos Osvaldo Caló (piano), Juanjo Mosalini (bandoneón), Sébastien Couranjou (violín) et Éric Chalan (contrabajo). En 2005, vuelve por primera vez a Argentina y se encuentra, 28 años más tarde con un inesperado éxito tras cada uno de sus conciertos, tanto público como mediático. La prensa lo tilda de "dedos mágicos". Llevará a cabo dos giras más en su país, en 2006 y en 2009.

El álbum DVD "5" (Chant du Monde/Harmonia Mundi, 2007) encuentra pasadizos entre el rock, el tango y la música contemporánea en un ejercicio de desestructuración del tango tradicional. La prensa francesa resalta la sutileza y la intensidad de su manera de tocar, al igual que le creatividad de sus composiciones. En Argentina, «entra» en la enciclopedia LA HISTORIA DEL TANGO - Siglo XX (Ediciones Corregid

or). En 2011, conjuntamente a la creación de su propia estructura de producción, TG&Co, radicaliza su estilo irreverente en las composiciones de su nuevo álbum, "Ítaca", al igual que en su espectáculo para septeto, Le Tango d’Ulysse, presentado el 5 de enero de 2012 au Théâtre de la Ville (Paris) - (puesta en escena: Laurent Gachet). Télérama le otorga ffff a su nuevo album « Encarnado, virtuoso, insolente, iconoclasta y futurista: el tango de Tomás Gubitsch, entre jazz, rock y música clásica, es todo esto a la vez.» Su «compañía» actual de músicos está compuesta por Juanjo Mosalini (bandoneón), Eric Chalan (contrabajo), Gerardo Jerez le Cam (piano), David Gubitsch (electro-libre), Iacob Maciuca (violín), Marc Desmons (viola) et Lionel Allemand (violonchelo).

En 2011, conjuntamente a la creación de su propia estructura de producción, TG&Co, radicaliza su estilo irreverente en las composiciones de su nuevo álbum, "Ítaca", al igual que en su espectáculo para septeto, Le Tango d’Ulysse, presentado el 5 de enero de 2012 au Théâtre de la Ville (Paris) - (puesta en escena: Laurent Gachet). Télérama le otorga ffff a su nuevo album « Encarnado, virtuoso, insolente, iconoclasta y futurista: el tango de Tomás Gubitsch, entre jazz, rock y música clásica, es todo esto a la vez.» Su «compañía» actual de músicos está compuesta por Juanjo Mosalini (bandoneón), Eric Chalan (contrabajo), Gerardo Jerez le Cam (piano), David Gubitsch (electro-libre), Iacob Maciuca (violín), Marc Desmons (viola) et Lionel Allemand (violonchelo).

Tomás Gubitsch se encarga de diversas "actiones socio-culturales", como la reciente en Romainville durante el año o en Massy en 2010.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)